book tour dates, the moral importance of good taste, leslie jamison

I’ve said it many times, in many different forums, in many different ways, and I will say it again: making writers talk, socialize, or leave their homes is cruel and unusual. Writers are creatures of their desks, or at least, this writer is a creature of her desk. As I’ve also said before, and as I will no doubt have many occasions to say again, I write precisely because I find talking so miserably inadequate. As I’ve also said before and as I will go on repeating forever: Nabokov, who insisted on writing out answers to interview questions in advance, had the right idea. The caveat that I wish I could append to every conversation I ever have is: I don’t know if I mean anything I say, because the way I figure out what I mean is by committing words to the page, and if I do accidentally mumble something I later discover that I mean, I won’t do nearly as good a job of formulating it as I would have if I were writing about it. Should I get this printed on a tee-shirt?

I was talking to a friend recently about how odd it is that we seem to want to make books into everything but what they are, which is of course texts to be read. We listen to recordings of people reading them; we listen to writers blathering on about them on podcasts; we watch filmic adaptations of them. I would like to suggest that we try reading them for a change—not, of course, because film is bad, but because writing is also good.

Still, people persist in the perverse and maybe slightly sadistic practicing of compelling writers to talk extemporaneously. Maybe they relish the squirming spectacle of it all; maybe they want to see a person who is usually such a precious perfectionist about words when she is called upon to just spew the wretched things out.

All of this to say: promoting a book involves talking. No way around it, unless you’re an eccentric genius, and I’m not. I suffer every day, for many reasons, from the fact that I fail be Nabokov. But I want people to read my book, and I’m grateful to Holt for promoting it, so I talked, and I will talk again.

I talked in this interview to my friend Nicholas Russell, an excellent writer and a generous and thoughtful interlocutor. Do I mean what I said (with my voice, not in writing)? As usual, I don’t know, but I do think I mean that “it really matters if somebody has bad taste,” and that indeed this is the central premise of the critical enterprise: https://defector.com/it-really-matters-if-somebody-has-bad-taste-an-interview-with-book-critic-becca-rothfield

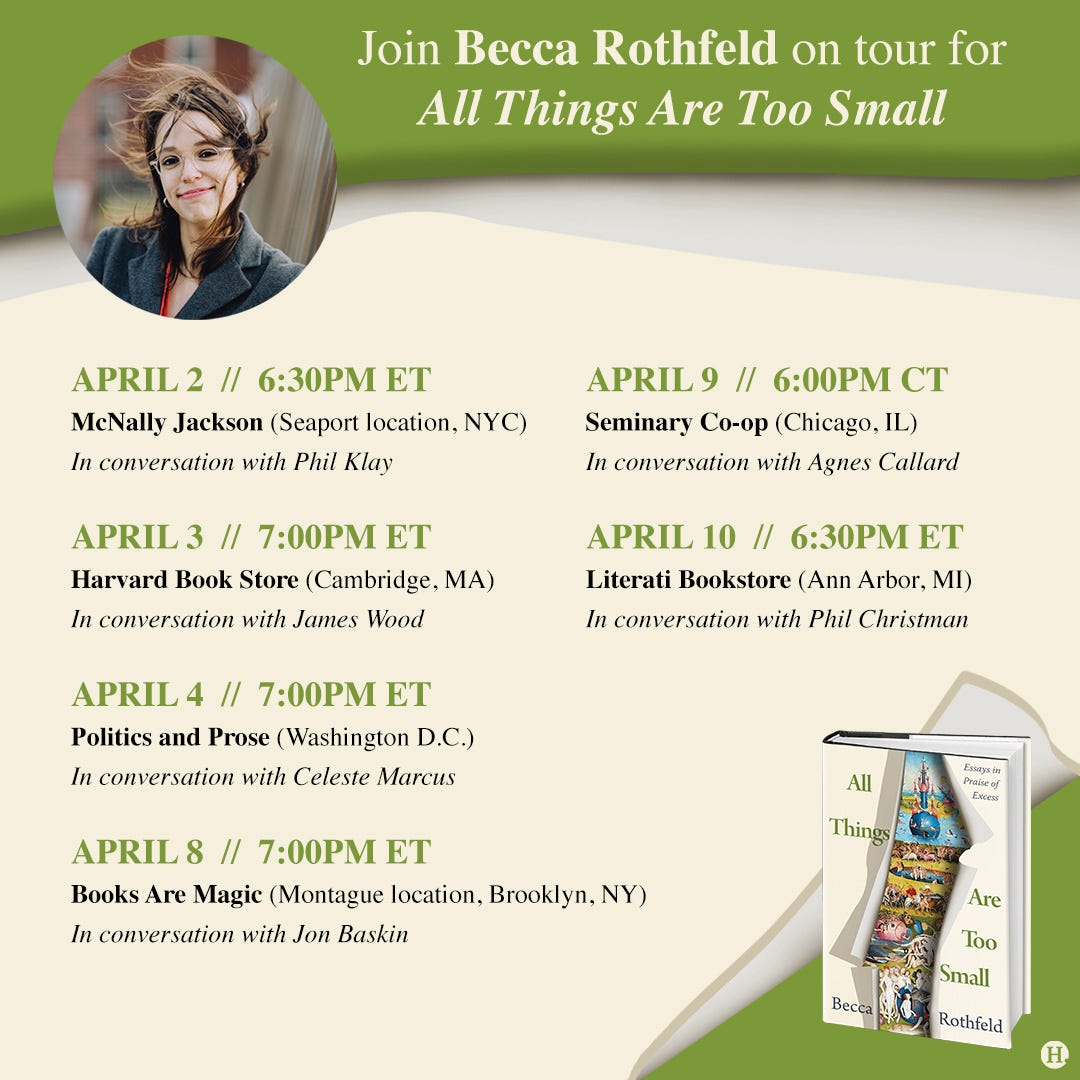

I will also be talking (probably poorly, but with great enthusiasm, and hopefully in a series of appealingly maximalist new dresses) on book tour. Here are the dates. I would prefer that you order the book and read it than that you come to a talk about it—after all, I labored for over a year in an effort to get all of those words just right—but I would love to see you at a talk provided you don’t make the mistake of thinking I mean what I say. My interlocuters are great, which is another draw. Here is the info.

Finally, I have written a few things since I last bombarded you, which I try not to do too much. (Bombarding people is also an unavoidable part of book promotion.) Most recently, I wrote about Leslie Jamison’s new memoir. Almost everyone who has reviewed it has liked it, but unfortunately, I did not. Here’s the piece: https://www.washingtonpost.com/books/2024/03/05/splinters-leslie-jamison-review/

You might be interested in this essay by Claire Kirwin, "Value Realism and Idiosyncracy", in which she argues that even matters such as chocolate vs. vanilla are matters of objective value: https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MHbJEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA24&ots=Y26lZmOuHY&sig=fwG3uX0iRcofIZjHQ2cA3rw1cFc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

On Kirwin's account, idiosyncracy of taste arises from idiosyncracy of value expertise. The chocolate lover possesses expertise in the value of chocolate that the vanilla lover lacks (and the same goes for artforms, genres, and specific works that are valuable but not universally beloved). If that's right, then the difference between the disagreements of idiosyncratic taste and disagreements in aesthetic judgement might be a difference in the degree of public access to the relevant aesthetic reasons (rather than, say, a difference in kind based on whether there is objective aesthetic value at issue).

Literati! So excited. (As cruel and unusual as it is to make writers talk.)